The Present of the

Future Past: On What Can Be

Stewart Home, “Writing about Writing”

Navigating

the seas in which all stories meet in the communication flux demands devising

tools for expressing one’s voice without necessarily claiming newness in the

strict sense of the word. How then, one wonders, can the past narratives

acquire the voices in which to speak here and now from the recuperated future?

How can the communication channel be freed from contaminating noise, so the remix

can speak clearly in the intersections of the time axes? McKenzie Wark:

Hacker

history does not need to be invented from scratch, as a fresh hack expressed

out of nothing. It quite freely plagiarizes from the historical awareness of

all the productive classes of past and present. The history of the free is a

free history. It is the gift of the past struggles to the present, which

carries with it no obligation other than its implementation. It requires no

elaborate study. It need be known only in the abstract to be practiced in the

particular. (A Hacker Manifesto [097]

square brackets in original)

In

“Dead Doll Prophecy” Acker explicates her hacker tactics. She discloses

particulars of the legal battle fought over the four plagiarized pages from a

novel by Harold Robbins. How abstract

hacking needs to be in order to be practiced in the particular without legal

repercussions? How many generations need to pass on their gifts so that one day

today can be the history of the free? How does such history write itself?

Acker’s

story is a testimonial about the generation of a piece of writing that entailed

legal action and caused a series of disheartening, legally futile, defenses: “Understood

that she had lost. Lost more than a struggle about the appropriation of four

pages, about the definition of appropriation. Lost her belief that there can be

art in this culture. Lost spirit” (33). On the one hand, plagiarized pages

inspire the poet to question her own literary creed and, on the other, to

suspect the literary establishment’s doctrine. Both have a paralyzing effect on

her because The law is murky and kafkaesque experience precludes her inability

to understand of what she is guilty (30).

In

the story, the character Capitol makes dolls. The characters of the dolls

re-enact the protagonists of the allegedly actual events: the poet, the

publisher, the journalist, the dead doll. The characters of the dolls symbolize

various aspects of the life of a writer in the society colonized by commodity:

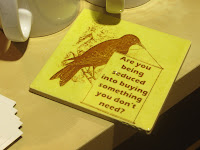

”HERE IT ALL STINKS […] ART IS MAKING ACCORDING TO THE IMAGINATION. HERE BUYING

AND SELLING ARE THE RULES: THE RULES OF COMMODITY HAVE DESTROYED IMAGINATION” (29).

The

poet sets out on a journey into the literary world. She practices her writing

according to the founding belief, instead of conforming to the founding fathers

of the trade. She believes that writing has nothing to do with the rules they

invented and everything to do with freedom: “Writing must be for and must be

freedom” (“Dead Doll Prophecy” 27). For

her to be free means to refuse the advice from the elders. In particular, the Black

Mountain bards inform her that a poet must find his own voice. She finds it to

be counterintuitive because such voice would define her in an excessively

dispiriting way--the way that would make her unable to recognize her own voice.

What

is more, she feels that determining such voice would affect her sense of

authority. Specifically, following the Old Masters’ sagacious suggestion would

be an act of succumbing to the patriarchal authority, against which she, in

fact, rebels. That would mean acknowledging god-like figures, and such

recognition offends her sense of power and divinity: “All these male poets want

to be the top poet, as if, since they can’t be a dictator in the political

realm, can be dictator of this world” (21). Approving of their quasi-godliness would be a

self-sacrificial act that she finds…well, just out of the question: “Deciding

to find her own voice would be negotiating against her own joy” (22).

Instead

of a demigod, she decides to be who she is—a writer: ”Wanted only to write […] To

hell with the Black Mountain poets, even though they had taught her a lot”

(22). The writer doll detects that the discussion is out of focus. Like the

grey law, the Black Mountain poets’ rhetoric disguises the narrative of a

different kind: “Knew that none of the above has anything to do with what

matters, writing” (34). She learns what

heritage is and what to do with it. She learns that those who do not

inherit—hack. McKenzie Wark: ”The hacker class is not what it is; the hacker

class is what it is not—but can become” (A

Hacker Manifesto [045] square

brackets in original).

: “Style can be a limitation and a burden” (William

S. Burroughs, “Creative Reading,” The Adding

Machine 39).

: “Style can be a limitation and a burden” (William

S. Burroughs, “Creative Reading,” The Adding

Machine 39).

Yes,

if it is practiced in a calcified form. But, then, one wonders whether it can

be called style. In any event, in order to distance herself from the ossified

perception of writing, she centers her literary persona around negation. The

poet suspects that the criteria determining what good literature is correspond

to that what qualifies a book to win a literary prize (22). Pornography,

science fiction, and horror novels, according to the literary standards, cannot

be classified as good literature. In response, she opts for “both good

literature and schlock” (22).

The

writer doll does not trust the bards’ supposed cleverness. She feels that what

is commonly perceived as cleverness is blind to its own susceptibility to

social control and manipulation. For that reason, she redefines her literary

persona based on negation: ”Decided to use language stupidly. In order to use

and be other voices as stupidly as possible, decided to copy down simply other

texts. Copying them down while, maybe, mashing them up because wasn’t going to

stop playing in any playground. Because loved wildness” (23). Eventually,

Capitol decides not to make dolls any more”: “CAPITOL THOUGHT, THEY CAN’T KILL

THE SPIRIT” (34).

Before

that climatic moment, the writer doll realizes that part of her writing tactics

is multiple offence: “Offended everyone” (22). The dilemma remains how the

reader can respond to an offensive text. To that perplexity Robert Glück has an

answer. In “The Greatness of Kathy Acker”

(Lust for Life: on the Writings of

Kathy Acker), he writes about the first encounter with Acker’s text as a massively

confusing and unsettling reading experience. First, it didn’t reveal anything.

Nor did it bring consolation. It inhibited any typical response. It is small

wonder, because it aims at subverting literary conventions by destabilizing the

reader, “keep[ing] the reader off balance” (46). It disables identification

with the text (47). It suspends belief in the text.

Glück

first realizes that reading Acker’s fiction is an oneiric experience. He also

decides that in the story, it is repetition that has a dream-inducing effect. It

is the repeated description of a dream in Acker’s I Dreamed I Was a Nymphomaniac that makes the reader question one’s

perception. The passage that describes a dream Glück finds intriguing. The

doubling of words makes him feel anxious because he cannot understand the

reason for that discursive self-proliferation. He is not able to comprehend it

because he cannot identify a possible reason for the writer’s strategy. Her

intentions at that moment are completely beyond his imaginative and mental

capacities. That disruption of the communication between the reader and the

writer is a source of bewilderment and sadness. It arouses a feeling of

loneliness, of being “lost in strangeness” (46). In that instant, the reader sees

no sane way to respond to a psychotic text: “a text that hates itself, but

wants me to love it” (46). The intention of the writer might be forever beyond

the reader. But, what is experienced as the text’s invitation to be loved

despite it hating itself, can certainly reinforce the reader’s decision to

ignore such a wish. What the reader can do is endure in suspending disbelief in

one’s otherness. And to love the reading experience for reconfirming such an

insight.

Subjectivity,

authority, and identity seem to be pivotal to Glück’s analysis of that revelatory

encounter with the text:

When

I lost my purchase as a reader, I felt anguish exactly because I was deprived

of one identity-making machine of identification and recognition. I gained my

footing on a form of identification that was perhaps more seductive, a second

narrative about Acker manipulating text and disrupting identity. To treat a hot

subject in a cold way is the kind of revenge that Flaubert took. Acker’s second

narrative acts as a critical frame where I discover how to read the work: the

particular ways in which a marauding narrative continually shifts the ground of

authority, subverting faith in the “suspension of disbelief” or guided daydream

that describes most fiction. (47)

:”Does the writer play fair with the reader?” (William S. Burroughs, “Creative

Reading,” The Adding Machine 42).

:”Does the writer play fair with the reader?” (William S. Burroughs, “Creative

Reading,” The Adding Machine 42).

Yes.

The reader is inspired and patient enough to recall that discourse is a means

of social control and manipulation. Acker’s text in particular makes manifest the

ways in which authority can communicate its power and what possible responses

to it can be. Her work demonstrates how voices of resistance can be defined and

articulated. She delineates the social margins aware of their otherness. The

awareness of one’s marginalization defines the authority:

Acker

takes revenge on power by displaying what it has done; she speaks truth to

power by going where the power differential is greatness, to a community of

whores, adolescent girls, artists, and bums, the outcast and disregarded […] If

hegemony defines itself by what it tries to exclude, then the excluded merely

need to describe themselves in order to describe hegemony (48).

And they do. In voices.

In shadow talk. The self-abhorring text that wants the reader to love it is

also the text that wants the reader to know that it is fiction. It is the

authority that wants to be dethroned. That wish the reader can satisfy.

Postfuturist storytelling bears witness to the double blessing called language

that savagely, but generously, reveals its duplicity. On the one hand, it is a

source of confusion, control, oppression, and suffering; on the other hand, it

provides room for its own remixing. Through such eerie oscillations one finds libratory and redeeming powers of language. As

one reads, one recognizes text to be, by definition, in the service of the

sovereign—language. As one uses language to communicate, it occurs to the

interlocutors that the communication channel is polluted. That awareness

ensures resistance against contaminating noise. That subtonic ecorebellion is a

means of remixing the noise.

Language epitomizes the intensity of consumption and creation. Language

is threatening and friendly. In language, it is possible to argue.

Alternatively, one can also share in language. Language is elusive, like its

fluctuating laws, but it mercifully recuperates the right to the remix of the

self-inducing confusion. It teaches how to look at both sides of imperfection:

one’s own and everyone else’s. By showing its own limits, language indicates

the limits of the human grandeur and reaffirms human potentials. It does so by resisting

the belief in the possibility of replication. It shows that a replica is an

impossibility by reanimating the stigmatized belief in authenticity.

:”Does the writer have a distinctive style?” (William S. Burroughs, “Creative Reading,” The Adding Machine 39).

:”Does the writer have a distinctive style?” (William S. Burroughs, “Creative Reading,” The Adding Machine 39).

Yes.

It tells about the vision of reindividualized humans, engaged in creation and

activism, vitalized by and inspiring solidarity and creation—the rebirth of the

human face through alternating cycles of silence and noise defining resistance against

the cannibalist culture of competitors and nihilist greed, as described in

Eagleton’s The Meaning of Life: A Very

Short Introduction (2007):

As for wealth,

we live in a civilization which piously denies that it is an end in itself, and

treats it exactly this way in practice. One of the most powerful

indictment of capitalism is that it

compels us to invest most of our creative energies in matters which are in fact

purely utilitarian. The means of life become an end. Life consists in laying

the material infrastructure for living. It is astonishing that in the

twenty-first century, the material organization of life should bulk as large as

it did in the Stone Age. The capital which might be devoted to releasing men

and women, at least to some degree, from the exigencies of labour is dedicated

instead to the task of amassing more capital. (155)

Acker’s

uncompromisingly disobedient voice is a NO to such culture. In that voice she

exemplifies a-proprietary writing of history. At the same time, in her shadow

talk, it is a YES to remixing it. To reclaim human dignity. In Leslie Asako

Gladsjø’s movie Stigmata: The Transfigured Body (1992), Acker expresses her

discontent: “If I had to spend all the time thinking what I cannot do, I

wouldn’t be able to live.” This statement encapsulates resistance to oppression,

reconstructing the axes of domination, refocusing the power relations narrative,

and redefining subjectivity. Acker’s stories show how it feels to be alive

today in the culture that is not exactly

a place that provides room for an impassioned immersion in play and creation.

But can be. As pieces of fiction, Acker’s stories might want to be read. Acker’s

metacritique is performative. The reader wants to reanimate it. The reader sees

Acker’s writing as an instance of storytelling from the dark lands that draws inspiration

from the transformative power of the world of letters, turning the temporarily

contaminated communicational tunnel into the green communication channel and

celebrating the greatness of the human spirit.

Off- Heritage Song(s): Avant-Garde Revisited

and Remixed

Epitaph/Epigraph: ye Roots of

Uprouting[1]

“Death is

the loss of love.”[2]

Dehumanizing. ”Exile whose other name is Delayed Death.”[3]

Disgust. “Robot fucking. Mechanical

fucking. Robot love. Mechanical love. Money cause. Money

cause. Mechanical causes. Possessiveness habits jealousy lack of privacy wanting wanting

wanting.”[4]

Has

New York/U.S. lost its hopeful appeal? Forgotten a possibility of rebirth from

the jazz era, the obscure countercultural charm of the Beats, fervor of the

civil rights movement, revolutionary NYC downtown noise of the 1970s…and the

magic of rock’n’roll? Suffered from the amnesia affecting the core ingredient

of life? ”If I knew how this society got so fucked up, maybe we’d have a way of

destroying hell.”[5] “Even in the face of something like gravity, one can jump at least three or four feet in the air and even though gravity will drag us back to the earth again, it is in the moment we are three or four feet in the air that we experience true freedom.”[6] Perhaps it’s not about knowing in the strict sense of the word. More likely, it's about the twist.Postfuturist at that. Methinks.

[1] Like the interludes,

sections 3.3.1 and 3.3.2 demonstrate inspired writing/writing through affect,

as explained in Chapter One.

No comments:

Post a Comment